When you identify a problem, focus on the solution instead… but be ready for it to be worse than what’s already in place.

Over the years, I have heard a lot of criticism on a vast number of topics. You don’t like a company policy? Complain about the problem. You don’t agree with a law? Complain about the problem. Don’t like how a process in your organization is conducted? Complain about the problem. While complaining about these problems is valid, when you identify a problem and fail to offer a solution, I don’t find it particularly constructive or entirely useful. Solutions are more challenging because they require you to take some ownership and invite criticism on your own ideas or even your original complaint. I’ve got an example of exactly that that I observed in my Air Force career during Professional Military Education (PME).

I’ve learned many valuable lessons from PME, despite how endlessly en vogue it is for students to express their distaste for it. In this case, the lesson learned was a validation of my aforementioned preference for solutions over problems. Expanding, I identified two key take-aways:

Sometimes the solution that’s already in place – however problematic – may be the best worst solution.

- The leaders who implemented that solution likely had the best intentions.

First, let’s discuss how PME led me to these reflections.

The Best Worst Solution

One of the implied goals of PME is to bring together military personnel from a broad swath of occupational specialties and geography to exchange ideas. In this case, it was when I was attending the Noncommissioned Officer’s Academy (NCOA) in 2015. NCOA focuses on honing the leadership and management skills of Air Force Technical Sergeants (E-6s) and preparing them to ascend into the senior noncommissioned officer ranks (E-7 and above). While one typically attends one of nine NCOA campuses around the world based on your geography, my class was one of the earliest in a new curriculum that required additional prerequisites and wasn’t yet employed across the other locations. This offered an unusual opportunity to talk to fellow Technical Sergeants from all around the world. My class had Airmen stationed in Germany, Japan, Alaska, Hawaii, and all across the United States, providing a significant breadth of perspective.

Bringing together personnel of diverse backgrounds to seek common problems and develop solutions helps Airmen build and broaden their sense of cohesive identity. It allows the aircraft maintainer to realize that the personnelist and medical technician contribute to the same fight as them… and share many of the same challenges. Encouraging them to act as a think tank occasionally produces something of value for the broader force, but that’s largely a byproduct.

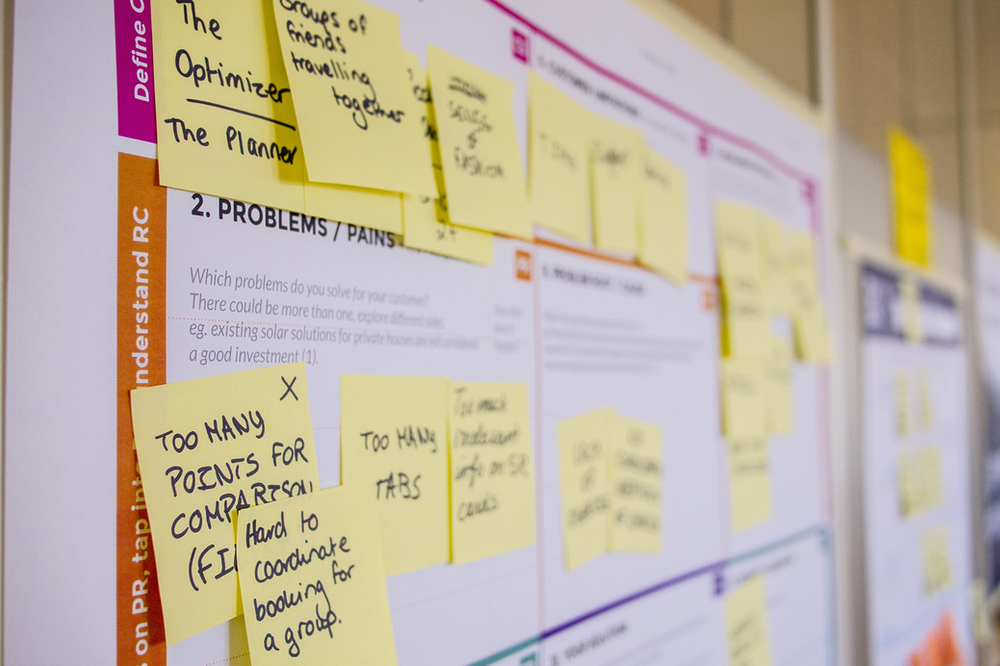

In several working groups, the instructors would ask us to determine what Air Force-wide problem we wanted to address and then facilitate us in using a structured problem-solving process to generate a possible solution. Deciding on a common problem was shockingly easy as everyone ran through the same typical pariahs: enlisted evaluations, fitness assessments, computer-based training, and even PME.

Spoilers: almost all of the solutions were utterly terrible. They often required unrealistically high costs, excessive senior leadership oversight, burdensome bureaucratic management, and/or unfeasible technical solutions. As I listened to presentation after presentation, it dawned on me: here is a room of hundreds of young tactical-level leaders creating profoundly flawed solutions to the common problems they directly experience. (Before you think I’m just dragging my peers, I can assure that even though I felt passionate about my solutions at the time, they were also terrible.) Is it possible that our current solution – as problematic as it is – is the best of all of the worst possible solutions? It’s not to say that we shouldn’t strive to acknowledge these issues and work to improve them, but maybe those senior leaders that put these policies and programs in place did the best they could at the time? It’s possible that what we currently have in place is the best worst solution.

The Road to Hell

It is said that the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and I would add that organizational policies are no different. Any organization with a sufficiently diverse and large number of people will produce policies that work poorly for a portion of the organization or result in unintended second and third-order effects. What I saw in our Air Force NCOA working groups were teams of passionate and motivated Airmen pushing hard to tackle complex problems… and failing. Despite their failures, I couldn’t once question their intentions, which led me to my next epiphany: senior Air Force leaders are unlikely to be hostile to our issues, and their intentions can be trusted, even if their policies are questionable.

While this may seem apparent to some, this was a soothing salve for my deeply-skeptical mind. Like many of my peers, I worked at honing my technical craft and performed my mission while cynically assuming that our senior leaders were just a bunch of out-of-touch old fogies incapable of understanding our issues on the line from atop their vaunted ivory towers. Watching my peers challenge the objectively problematic solutions with ideas that were even worse directly challenged that idea.

To hear me talk about senior leaders now, one might assume that I am drunk on the “Kool-Aid” and have become entirely naive. I still question some decisions from a functional standpoint, but I no longer doubt the goodness of their intentions. With rare exceptions, I have come to explicitly trust that decision-makers have the best interests of their personnel and mission at heart.

Conclusion

While every organization has its problems, it has become my habit to challenge those who feel comfortable complaining about them (particularly within my own organization) to offer solutions and critically discuss them. In some cases, their solutions genuinely represent an improvement; however, in most cases, it’s an illustrative opportunity to help them see that we’re already sitting on the best worst option. We can certainly acknowledge and admire the flaws, but focusing on solutions can help us accept them and improve our trust in those who created and implemented them.