One Bullet Away: the Making of a Marine Officer is a story that many vets have heard, but is a beneficial read for young military leaders, regardless of branch.

Published in 2005, One Bullet Away: The Making of a Marine Officer by Nathanial Fick is a solid read that is equal parts military leadership primer, hero’s journey, and historical perspective on the early days of Operations ENDURING FREEDOM and IRAQI FREEDOM. I first learned about this after reading through the helpful annex of recommended reading at the end of Secretary Mattis’ Call Sign Chaos. His tale isn’t entirely unique, but he weaves it skillfully and offers several useful lessons and their combat applications throughout.

Training for War

“If safety were paramount,” Whitmer declared, “we’d stay in the barracks and play pickup basketball. Good training is paramount.”

The first thing you need to know is: don’t let the title fool you. While Fick shares things from the narrow lens of a Marine Corps officer who served four years and separated as a Captain, his thoughts and perspective are still valuable to a Soldier, Sailor, or Airman – officer or enlisted. He begins his journey at Dartmouth University, where he decides to take a different turn than many of his peers and turn his talents toward the profession of arms with the Marine Corps. Graduating in 1999, he believed strongly in the Marines’ ethos and drove mercilessly threw himself toward his goal of becoming an infantry officer. Throughout his training, his sharp memory serves up several useful lessons that would later serve him well on the battlefield, as well as prepared him emotionally for some of the moral hardships of military leadership.

Afghanistan

“You can’t volunteer to go to war and then bitch about getting shot at.”

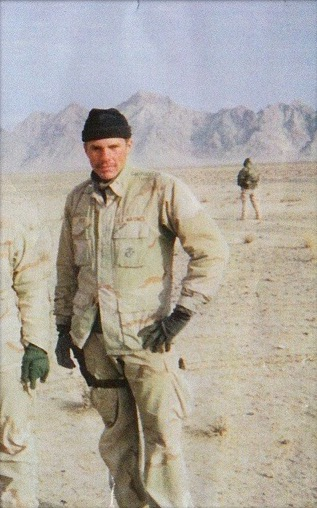

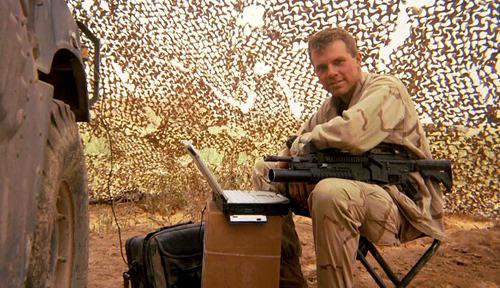

From Officer Candidate School, through Basic Combat Training, on up to the Infantry Officer Course taught Fick many skills that – in much of 2001, most saw as less important than how to create a good PowerPoint slide. Shortly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, as a platoon commander in the 1st Battalion 1st Marines, he and his team deployed to Afghanistan in the early days of Operations ENDURING FREEDOM. After returning to the states in March of 2002, he was selected for training to become a Reconnaissance Marine, completing it just before assuming command of Second Platoon of Bravo Company under the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion. Just like his last assignment, he didn’t receive much time to rest before receiving orders to deploy as part of the initial wave into Iraq in 2003 to dismantle Saddam Hussein’s corrupt and murderous regime.

Iraq

“The bad news is, we won’t get much sleep tonight; the good news is, we get to kill people.”

The story’s third act makes up the meat of the book, detailing Fick’s team’s victories on the leading edge of the invasion force. More importantly, he also delves into the moral conundrums that challenge every thoughtful combat leader. In one case, he and his team were tasked with defending an airfield and treating anybody who approached as hostile, meaning that all Rules of Engagement (ROEs) that would otherwise restrict their fire were off the table. Tragically, this resulted in the shooting of two young shepherd boys whose canes – at a distance – were mistaken for rifles in the heat of the moment. To Fick’s credit, he shows the greatest humanity, directly challenging his chain of command until he could get them to acquiesce to providing some level of care.

“Strong combat leadership is never by committee. Platoon commanders must command, and command in battle isn’t based on consensus. It’s based on consent. Any leader wields only as much authority and influence as is conferred by the consent of those he leads. The Marines allowed me to be their commander, and they could revoke their permission at any time.”

Another harrowing moment occurs later on, as Fick’s team is tasked with scouting out an old recreational area. They’re given a narrow four-hour window to operate, yielding little time for distractions as they quickly uncover evidence of Baathist (Hussein’s political party) use of the area as a post-invasion planning and staging area. Shortly after arriving, his team was intercepted by a desperate family with a young daughter whose leg was broken and dangerously infected. He gave his medic more time than he could offer, knowing that the young girl was likely injured by his fellow Marines and feeling a sense of obligation – both as a Marine and a human.

Despite Fick’s humanitarian desires, there was little either the local hospitals or the Marine Corps could do to provide aid. His medic irrigated the wound and provided a few days of antibiotics, before pointing them towards the closest Marine encampment. While he hoped that they would render assistance, he knew it was wildly unlikely and that the young girl would die. Running short on time, he and his team weren’t able to complete their reconnaissance mission and noted several locked warehouses that needed to be checked as they left.

The next day, another reconnaissance team was able to check the warehouses, discovering a cache of man-portable surface-to-air missiles. More importantly, it appeared that several had been taken in the last 24 hours. Afterward, Fick wrestled with the moral conundrum: how many helicopters over the next several months were shot down using the weapons that his team should have recovered instead of helping a young girl who would likely die either way? These are the kind of challenges that plague people during war, where there are no easy choices, and the only loser is your own humanity.

“Tactical catastrophes are rarely the outcome of a single poor decision. Small compromises incrementally close off options until a commander is forced into actions he would never choose freely.”

Like all classic hero’s tales, Fick’s resolves in the uncomfortable return home, somewhat confused by the bombast of color, carefree civilians, and worst of all: gratitude. Like many veterans, his stomach turned whenever he was thanked for “what he did over there.” War is an ugly and grisly business with a high cost for both those who die and those who must live with its scars.

Conclusion

To be clear, anyone who has spoken with a veteran in the last twenty years has heard some variation of Nathaniel Fick’s One Bullet Away: The Making of a Marine Officer. A bright young person becomes passionate about the profession of arms, chases after the dangerously rewarding parts of it, slowly becomes disillusioned by the awful choices he had to make while deployed, and finally returns to a home that might not ever feel the same. What makes this tale powerful is how well-delivered and approachable it is. Unlike other similar stories, Fick isn’t just talking to other service members and drowning you in jargon; he’s also speaking to civilians who are curious to hear the honest story of a tactical-level leader in modern conflict. He relates it in such a way that avoids all of the piss and vinegar that so many associate with the military – and the Marine Corps in particular – and offers a far more vulnerable perspective. I highly recommend this book to curious civilians and young officers or noncommissioned officers (regardless of branch) interested in expanding their understanding of effective tactical-level combat leadership.

“Complex ideas must be made simple, or they’ll remain ideas and never be put into action.”