What the Military can Learn from the State Department

A defining element of military indoctrination, training, and culture is the focus on victory. Sports analogies are common as we execute a “full court press” and “push to the end zone,” and we’re exhorted to not “leave anything on the field.” Every great military speech is utterly focused on victory at any cost and for good reason: the military’s mission is traditionally temporary in nature and designed to combat a presumably existential threat. n

Warfare since the end of World War II has challenged this. The Cold War and its associated conflicts created an environment where the existential threat was no longer the unlikely scenario of German tanks rolling through Los Angeles, but one where nuclear missiles from across the world could snuff out all life. It also characterized the conflict as one of ideas over mere survival. Instead of conflict taking place for resources or personal/political slights, we have now formally adopted the position that the military is a tool for combatting an idea. The ideas considered most threatening have morphed over time from communism to violent religious extremism, yet the challenge remains: how do you bomb away an idea? At what point can you declare victory and go home?

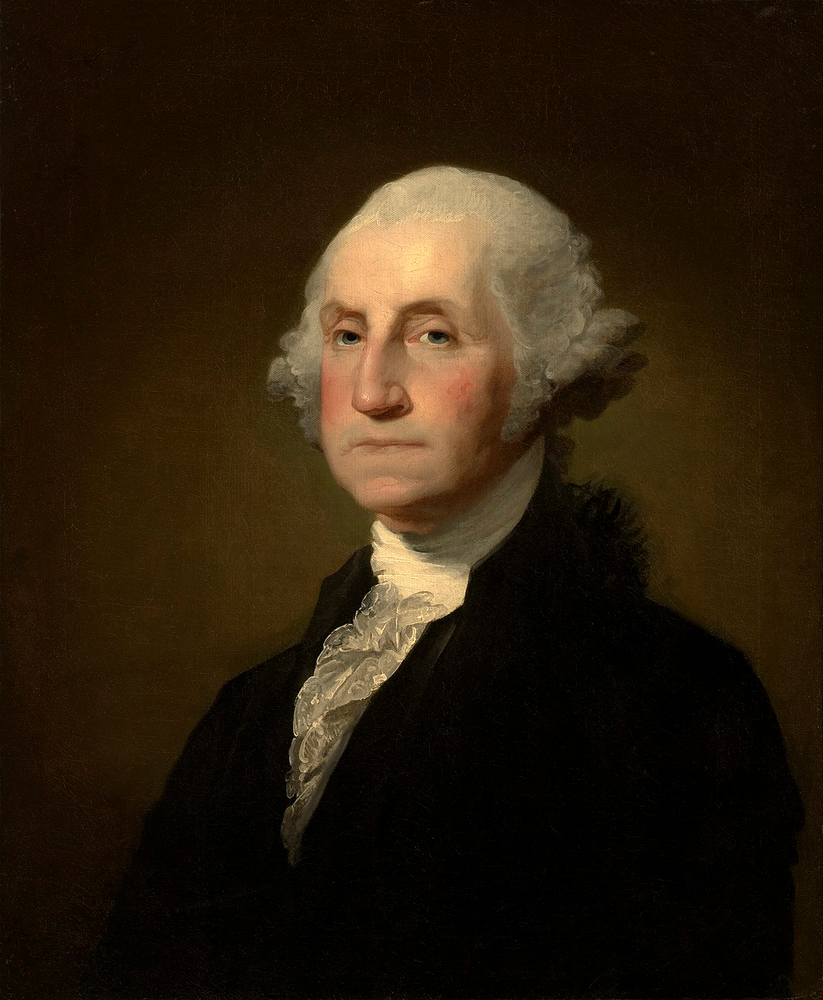

Washington’s Warning

In 1783, President George Washington wrote at length about his concerns regarding the organization and purpose of the military in Sentiments on a Peace Establishment. While he famously warned against the danger to liberty that a large standing army represented, he assented to its necessity to deal with nearby threats, defend foreign trade, and to protect military stores of weapons and ammunition. Additionally, he determined that the vast majority of the military should be made up of a “well-regulated militia” controlled by the states and train under a common set of rules and principles (giving the second amendment of the Constitution some well-needed context). Finally, he added that the military should build and protect stockpiles of arms and provide professional martial education.

Three key elements can be extrapolated from this essay:

- President Washington was wary of a large standing military with no mission.

- The military’s mission was primarily a temporary one, requiring occasional activation of its citizen-soldiers.

- He was extremely concerned over the building and protection of arms supplies.

Many of these ideas continue to proliferate through military culture to this day, from the close partnerships formed between active duty and national guard/reserve forces to the tight relationship between the Department of Defense and its arms manufacturers. While we could say that we’ve strayed pretty far from Washington’s concerns over a standing army, one could argue that our mission has become increasingly global in nature, and the numbers we have are still incredibly small given the size and scope of its mission.

When You Like Using the Hammer, Everything is a Nail

If you are a politician charged with making challenging foreign policy decisions, who do you turn to for solutions? There are many tools available, but primarily we talk about the U.S. Department of Defense, the Department of State, and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Since the end of World War II, an increasing number of solutions have been sought from the military over the other organs of international power. Why?

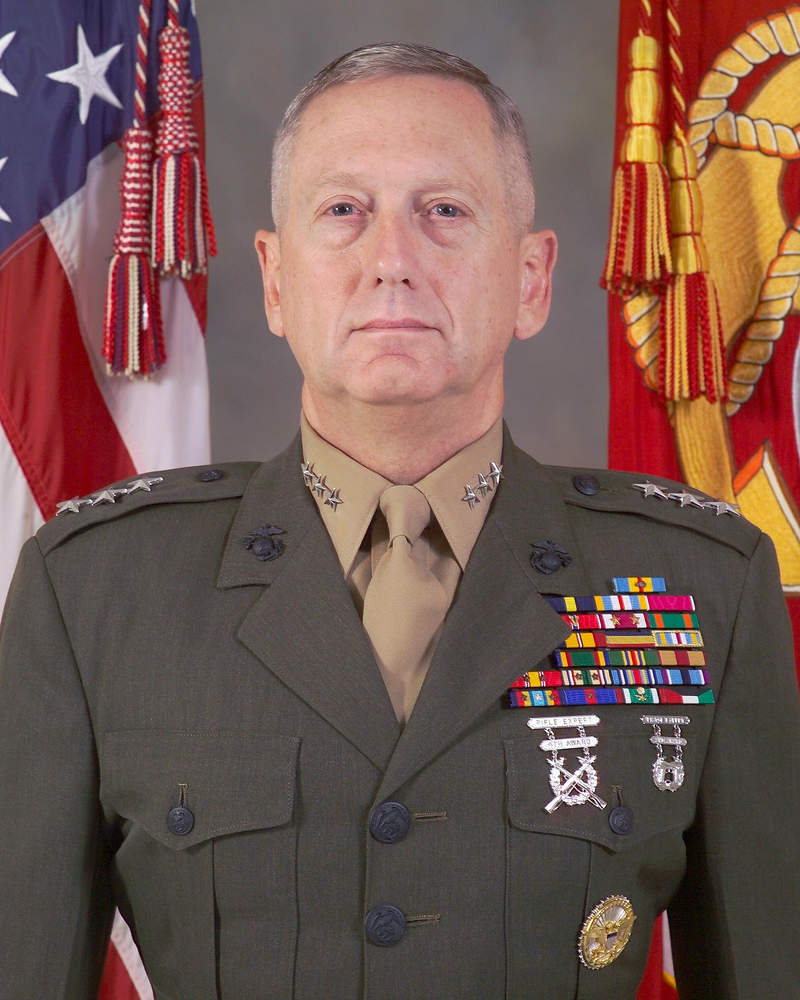

First, as mentioned above, the military is focused on victory. If a President asks for advice from their Secretary of State, they will hear “this will take a long time, will require a lot of pressure from many angles, and may result in unintended consequences.” Turning to their Secretary of Defense, they will hear one word: “Victory.” As a result, the DoD budget has soared while the DoS/USAID budget has continued to plummet. Secretary Jim Mattis (then the commanding general of U.S. Central Command) famously said, “If you don’t fully fund the State Department, then I need to buy more ammunition.” Despite this dire warning from a top general, as of the 2019 U.S. federal budget, the DoD requested $686 billion (and growing) compared to the combined DoS/USAID ever-shrinking request of $37.8 billion.

To put this interesting inequity into context, it’s useful to understand the legal authorities under how we execute U.S. foreign policy. In each geographic area, a single agency is designated as the lead while the others are expected to serve in supporting roles. In military terms, we may refer to that as the battlespace owner, though ironically, that role is rarely the DoD. Except in cases of war or extreme and limited circumstances, the DoS is always the lead agency, and the DoD performs all missions in that battlespace in coordination with and in support of specific DoS objectives. To put that in perspective, the lead agency responsible for executing the overwhelming majority of the U.S. foreign policy does so with just a portion of 5.5% of the DoD budget. It becomes comical at a certain point, and we need to ask who has de facto control of the battlespace despite DoS’s de jure role.

Thus, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy when a politician wants to find a solution for a foreign policy issue: reach for the well-funded hammer instead of any other tool. Even if a screwdriver would be better suited to the task, the hammer is coming out. Naturally, the hammer is lousy at driving screws, so the answer must be to spend more money on the hammer! This is how we achieve the victory that the military is uniquely-capable of delivering, right?

Fighting With What We Have

There’s an old adage that goes, “you must fight with the army you have, not the one you want.” Unfortunately, there appears to be no end to using the military to further peacetime foreign policy goals. The army we really want working toward furthering our foreign policy objectives is our State Department partnered with USAID, but short of that, service members need to retool how they approach problems to be effective partners – and if necessary – de facto battlespace owners. Critical to this is understanding the difference between process and outcome.

Outcome is simple, and the military knows it well. A crisis arises, the military organizes and fights it, it achieves victory, it pins on some medals, and goes home. By design, the military is utterly focused on achieving a desirable outcome, and all of its metrics for success are narrowly built around that. This is part of what has made the last twenty-plus years of conflict so disheartening to so many service members; we are craving an outcome. We deeply desire the victory that we have worked for. This is in sharp contrast to the basic expectations of our partners at the Department of State and USAID; they think and work in processes.

Process is about approaching problems patiently and iteratively. Unfortunately, it doesn’t yield the satisfaction of quick fixes. Instead, like a master gardener, process is focused on continual improvement and reassessment. By design, there cannot be a desired end state because it does not end. Instead, one has to appreciate the moment, savor the little incremental victories, and not feel crushed by the little incremental defeats.

If the military is going to thrive in the paradigm where political leaders continue to use it for diplomatic peacetime missions (in the guise of security cooperation), then it must adapt from being outcome-oriented to process-oriented. As it stands, it is funny to watch Defense and State personnel chase each other through an argument where the Defense official will ask what the desired end state is while the State official will get confused and try to explain what they are doing. While an outcome-oriented approach to foreign policy seems easy, history has shown that the desired outcome is rarely achieved. Even when it is, a litany of unintended consequences occurs, like the Cold War that blossomed in World War II’s wake.

Conclusion

Moving onward into the twenty-first century, we must recognize that wars are not fought using the same tools or culture they used to be. While President Washington was understandably wary of a large standing force, we have embraced it and deployed it. So enamored have we become with it and its nigh-unhealthy emphasis on victory – or outcomes – that we have become dependent on it to work towards our nation’s foreign policy objectives. Doing so has caused us to move further away from Washington’s ideals of a limited force of narrow purpose, as it eclipses its Department of State and USAID partners in budget, personnel, and de facto authority.

Understanding that environment, it is essential that the Department of Defense personnel realize what this means: we must shift our culture from being outcome-oriented to process-oriented. We must view conflict as a continuum, rather than black and white. We must also view conflict as a wave that rises and falls, rather than a progressive line that builds upwards until it collapses and never returns. Doing so will help us more readily understand and integrate with our interagency partners while also furthering our nation’s foreign policy objectives.